Introduction

Within the New Forest, over the last nine years, Forestry England volunteers have been busy collecting data for The Riverfly Partnership.

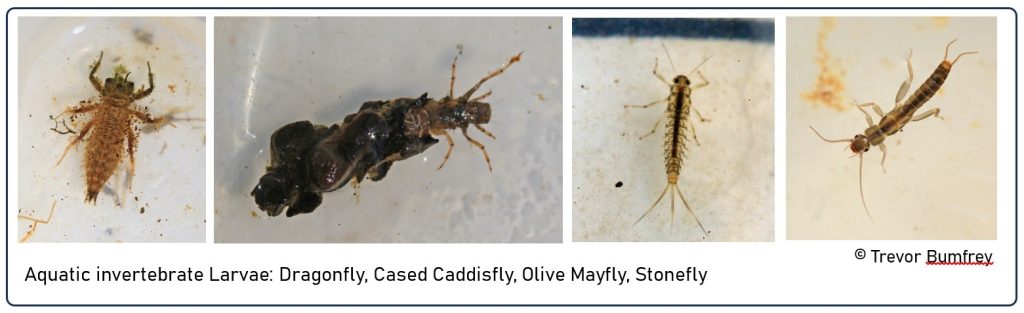

Members of the public – keen citizen scientists – are trained to identify and survey specific groups of freshwater invertebrates, whose diversity and numbers can tell us about the overall health and characteristics of our streams.

Analysing this data can help us to detect possible pollution events, and understand how river restoration can impact these small creatures.

At Wootton Riverine Woodland (where over 2.5 miles of the straightened channel of Avon Water was returned to its natural meandering course), we found little change in yearly scores pre and post restoration. We did, however, detect an increased number of recorded groups, possibly indicative of an increase in habitat diversity.

Research indicates that naturally functioning rivers contain more variable habitats (e.g., areas of different flow type/ bed material), and, thus, support greater species diversity. While interpreting relationships between aquatic invertebrates and river restoration is complex due to various influencing factors (e.g., climate variability), the increased habitat diversity at Wootton Riverine Woodland appears to have encouraged a wider variety of species to colonise the area.

About the projects

The Riverfly Partnership’s citizen science projects are designed to assess the health of rivers and streams in the UK through aquatic invertebrate sampling. Citizen scientists are trained to identify certain groups of freshwater invertebrates, whose diversity and numbers give an indication as to the characteristics and pollution levels of a watercourse.

Over the last nine years, we have been collecting Riverfly data with the help of some very dedicated volunteers. We started with the original Riverfly Monitoring Initiative (RMI – also known as the Anglers’ Riverfly Monitoring Initiative, ARMI) technique, which monitors eight pollution-sensitive invertebrate groups. The results are used to calculate an ARMI 8 group score (ARMI score).

Then, in 2019, volunteers were trained to undertake Extended Riverfly monitoring, which includes 33 invertebrate groups. This helps give a much more detailed and nuanced indication of river health. Based on the abundance of certain groups, and their sensitivity to pollution and other types of environmental stress, different scores are calculated. Known as ‘biotic indices’, these scores can indicate how much a site has been affected by variables such as organic pollution and silt content.

We’re analysing the data that has been collected, which is helping us to get a really good picture of the species diversity and abundance in some of the New Forest’s streams. Investigating how Riverfly scores have changed over time also helps give an indication of the impact of river restoration on freshwater invertebrate populations.

Read the case study below to find out more about some of the ways we are using this data.

Case study: Wootton Riverine Woodland

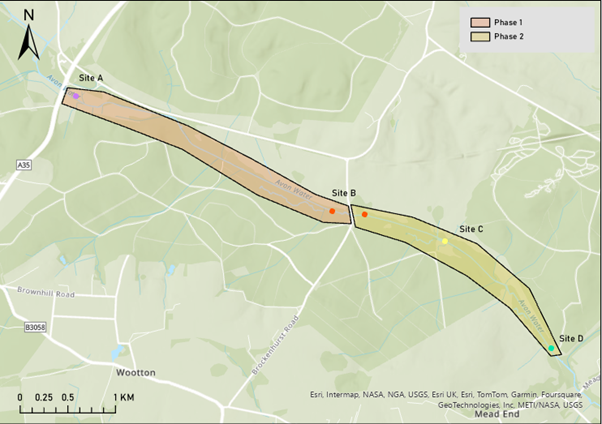

The Wootton Riverine Woodland restoration site encompasses a stretch of the Avon Water just north of the hamlet of Wootton. The watercourse was straightened in around 1860, leading to increased erosive energy and channel incision. This led to a deep channel with steep banks and spoil embankments, preventing water from interacting with the floodplain during high flows. Two phases of restoration were carried out to restore natural processes: Phase 1 took place upstream of Wootton Bridge, between 2016 and 2017; Phase 2 took place below Wootton Bridge between 2017 and 2018 (figure 1). Restoration involved reinstating the old meanders, filling in drainage ditches and removing spoil banks.

Riverfly results

Four Riverfly Sites have been sampled since 2016 (figures 1 and 2):

- Site A – Situated just below the A35, upstream of all restoration work. This area acts as a control site.

- Site B – Wooded area within the downstream extent of Phase 1 (2016-17). Due to difficulties accessing the sampling site, this was moved to just below Wootton Bridge in April 2022.

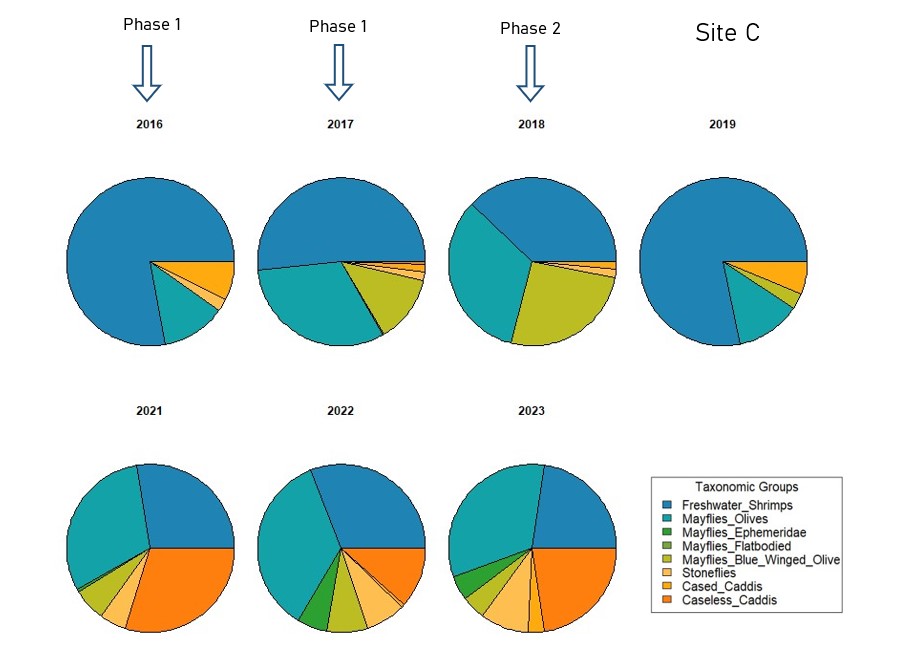

- Site C – Open area within Sheepwash Lawn. Phase 2 (2018) took place on the upstream and downstream reaches from this site, although the channel itself was not altered here.

- Site D – Downstream of Phase 2, just below a footbridge. No restoration work took place here.

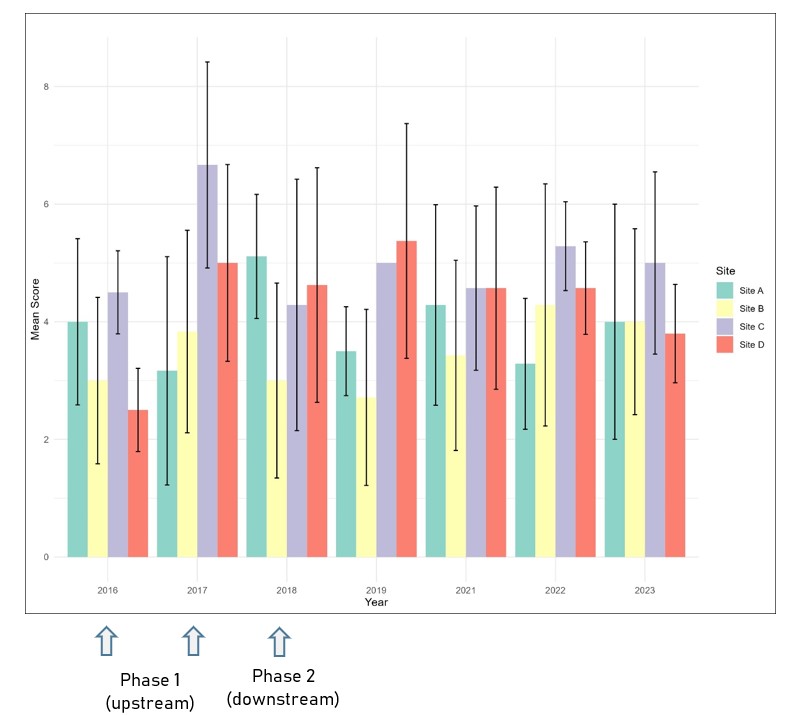

We ran statistical tests on the ARMI scores from these sites, making sure to take the sampling month into consideration, as aquatic invertebrate populations (and scores) can vary greatly over the season (e.g., see figure 5).

While ARMI scores varied significantly between the different sampling sites (e.g., Site C had, on average, a greater ARMI score than Site A and Site B), there was no statistically significant difference in ARMI scores between years for any individual site. These results suggest that restoration has had little impact on the average yearly ARMI score (figure 3).

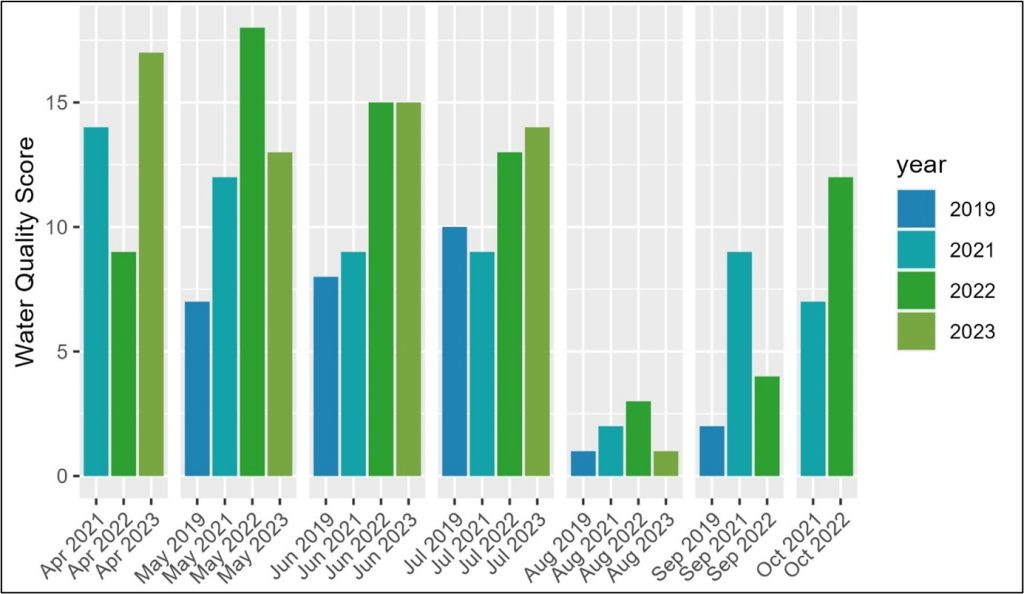

We then looked at the Extended Riverfly data, which has only been collected since the site was restored (2019-2023). Interestingly, we found that there has been a weak upward trend in Water Quality score over time at Site B (figure 4), with 2022 and 2023 exhibiting higher water quality scores than 2019. Site B is located at the downstream end of the Phase 1 restoration area. In the years immediately following restoration there may be a short-term increase in silt and sedimentation in the channel, which along with the general disturbance caused by the restoration work, may have impacted aquatic invertebrate populations, resulting in lower water quality scores. The higher scores since 2022 indicate the aquatic invertebrate population may have recovered from this disturbance. It is possible that the change in site location has partially driven this change.

Although the site characteristics are very similar, and the new site is located less than 100 m downstream, aquatic invertebrate populations can vary greatly even on small spatial scales, depending on factors such as flow type (Platt, 2011). However, ARMI data collected from both sites between 2016-2018 indicates there was no obvious difference in scores for these two sites. This suggests aquatic invertebrate populations may still be recovering from the restoration work. Further monitoring will help discern whether Water Quality scores continue to increase or stabilise at their current level.

In contrast, we found no evidence of trends in Water Quality score for the other sites. Yet, despite not seeing huge changes in Riverfly scores, we found that species composition has changed noticeably between years.

For instance, at Site C, the number of ARMI groups found increased from four in 2016, to seven in 2023, with the addition of Caseless Caddisflies, Ephemeridae Mayflies and Blue-winged Olive Mayflies (figure 6). Therefore, while this is not reflected in the Riverfly scores, this change does suggest river restoration has led to a greater diversity of habitats, enabling a greater diversity of aquatic invertebrate species to colonise the area.

Overall, relating changes in aquatic invertebrates with river restoration is challenging due to the myriad of other variables that can influence aquatic invertebrate populations (e.g., climate variables, pollution events), as well as difficulties finding sufficiently sensitive and informative indicator scores. However, encouragingly, the Wootton Riverine Woodland Riverfly results suggest the aquatic invertebrate populations studied were not negatively impacted by the restoration work, with some evidence that the area provides a suitable habitat for a larger diversity of invertebrate groups now. These results are supported by the findings from the aquatic invertebrate sampling done by BUG (Bournemouth University Global Environmental Solutions), who undertook aquatic invertebrate sampling from 2015 to 2021, identifying individuals to species level. They found that, apart from an anomalously low number of taxonomic groups in 2021 at the upstream site, numbers remained stable or increased over the sampling period.

Aquatic invertebrate monitoring is just one of many ways of monitoring river restoration success along with other methods. The HLS team is also mapping the habitats and carrying out vegetation surveys.

Find out more

Visit this page to find out more about the monitoring work being undertaken: Monitoring wetland restorations – HLS New Forest

References:

- Platt, J. (2011). Habitat complexity and species diversity in rivers. Ph. D. Thesis. Cardiff University. Available at: Habitat complexity and species diversity in rivers (cardiff.ac.uk) (Accessed: 16 April 2024).